Technology and time, from the average length of a song to worker productivity.

Contrary to popular belief, technological innovation in the last few decades has not increased worker productivity, but it has decreased the average length of a song.

This wasn’t written by AI, but isn’t that exactly what a nefarious AI would say?

Every disruptive technology brings a trepidation that stems from an innate human fear of replacement. In myth, media, and conspiracy, we play this anxiety out over and over again, imagining the threat of our own obscurity through reptilians, demons, robots, or other humans. While our fear of replacement is almost always irrational and unwarranted, when we fictionalize the fear it helps to collectively alleviate the feeling and minimize its spillover into the real world.

What makes this particular moment so unique, especially as it pertains to advancements in AI and automation, is the convergence of imagination and reality. For maybe the first time ever, everything we’ve feared, imagined, and depicted about our replacement by humanoid automatons looks less and less fantastical. But it’s not likely to happen in our lifetimes.

For the last few months, I’ve been experimenting with ChatGPT (I know, I know, me and every other guy you meet at a party). I’ve asked it to do an array of tasks from coding to writing to research and data analysis. What I’ve found is that it really lives up to its name: artificial intelligence. It can follow precise instructions, recycle structured language (i.e., code), and read data, but there’s really no creativity or ingenuity there. That quintessentially human intelligence comes from the people using it. Plus, it still writes an essay at a fifth grade level (no shade to any kids who might be reading).

For now, AI is like a calculator for the information age, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a disruptive technology with important implications for the way we produce and consume. From manufacturing to music, the relationship between technology, production, and consumption has been marked by cycles of expansion and contraction, and it’s possible that AI will send us into another expansion, but recent trends suggest we’re just now getting back to where we started.

Since the 1980s, workers have been more productive, but technology has not.

The prevailing assumption is that technological advancement means more productivity in an economy, because technology theoretically makes workers more efficient, allowing for more output with less input. The data suggest a more complicated story.

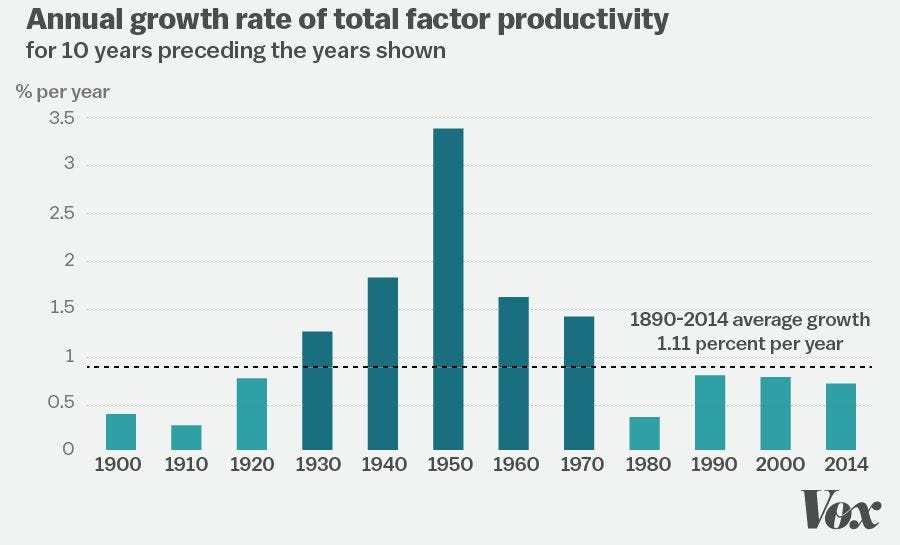

Two common measures of productivity are Net Productivity—the difference between the value of goods or services and the labor that went into producing those goods or services—and Total Factor Productivity—the economic output that can’t be accounted for by labor and resources alone, i.e., growth as a result of technological innovation.

While it’s true that Net Productivity, i.e., labor output, in the US has been increasing at a linear rate since the 1950s, Total Factor Productivity, i.e., technological output, has been stagnating. In other words, workers are more productive, but technological advancements are not contributing to that productivity. So, despite what seems like constant technological innovation, the idea that workers’ lives are better as a result is a myth. Workers are working harder, but their compensation is not commensurate with the output they’re producing.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, technology contributed significantly to productivity. These decades married industrial automation with the national war effort, ballooning US economic output, Net Productivity, and Total Factor Productivity (TFP). Following Vietnam War disillusionment, productivity dropped off dramatically even as computers started to find their way into the workplace. The last two decades of the 20th century, like the first three, never broke the 100+ year average TFP annual growth rate of 1.11 percent. Since the 1990s, that rate has continued to decline, even through Web 1.0 and Web 2.0.

While technology has a very real impact on production, it’s not always a positive or one-to-one relationship, because there are many factors—from wars to politics and pandemics—that help determine what that impact will be. In the end, it’s all about where technology fits in time.

The average length of a song is approaching 3 minutes … again.

In the case of music consumption, you can measure the impact of technology both over time and also on time. That is to say, consumption technologies have changed the ways that consumers interact with music over the years and those changes affect certain characteristics of music production itself, including track duration.1

Believe it or not, short-form consumption isn’t new. That’s really how recorded music started: short songs released one or two at a time. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the LP (long play), or what came to be known as the album, started to become the dominant music commodity, ultimately driving the average length of a song up by 60 percent.

Out of the TFP boom of the mid-20th century came more durable vinyl records and the cassette tape, which helped solidify the album’s staying power and set the recorded music sector on a trajectory that only the internet could reverse. In concert with this industry growth, the average length of a song on the Billboard Hot 100 also increased from around 2 minutes and 30 seconds to more than 4 minutes by the height of the CD era.

Each successive technological advancement in music consumption since 1999 correlates with a 25 percent decrease in track duration, ultimately taking the average length of a song from 4 minutes to just a bit more than 3 minutes—an average duration the Hot 100 hasn’t seen since the 1970s.

If we zoom in to just the last 15 years in music consumption, it’s worth noting that the release of TikTok does correlate with a 10 percent decrease in track duration in just three years. It took Spotify almost a decade to facilitate an 8 percent decrease. With pandemic lockdowns, which helped make TikTok a dominant medium for breaking new music, track duration hopped back up by 3 percent, likely because consumers were more online than ever and willing to consume longer content. Where track duration would be had we not had a pandemic is anyone’s guess, but I wouldn’t be surprised if duration had declined even more.

I’ve heard it posited by some very big players in the music industry that we’re not just back in a singles business, but we’re on the cusp of a “sub-singles business.” With younger generations largely consuming music in 60-second-or-less videos on TikTok rather than streaming on Spotify, it’s likely that average duration, at least in the mainstream, will approach the average of 2 minutes and 30 seconds the industry saw in the ‘60s. Over time, AI may help accelerate this contraction in time, but my hope is that every industry sees the real value of artificial intelligence: increasing Total Factor Productivity and lowering barriers to institutional knowledge—not replacing the human intelligence, heart, and soul of hard-working creators.

Information is abundant, and time is not—but that doesn’t mean we should only see the trees. The proliferation of information should help us see the forest.

Thank you to Elena Coelho for inspiring this article and making the data available for others to use. You can check out her report here.