Artist-centric, user-centric, or pro rata: How do musicians make money from streaming?

How musicians—and investors—make money from streaming largely depends on the models streaming platforms use to distribute royalties, so let's demystify them.

Music consumers may soon become retail investors.

In 2020, at the height of the pandemic, I graduated from NYU’s grad program in Music Business and Music Technology after turning in a Master’s thesis called The Spectre of Music Value: Value Revolutions in the Music Industry. The main thrust of my research explored how technology might be able to recapture music value for creators.

Ultimately, I concluded that the most likely route for value recapture via technological innovation was the development of intellectual property (IP) stock markets. Given the the influx of private equity and gamification in the music industry, I saw the development of public IP markets as an inevitability, for better or worse (imagine Robinhood as a streaming platform).

Within the last few months, The Orchard Founder and former Chief Information Officer of Warner Music Group Scott Cohen announced the rollout of JKBX, a platform that allows investors to buy shares in songs that they like or think will perform well.

JKBX is a platform for investing in shares of the income generated from music royalties. If you’re an investor looking to diversify your portfolio, that means an alternative asset class that has historically outperformed the S&P 500. And if you’re a music superfan looking for a deeper connection with the music you love, now you can turn your playlist into a passive income stream.

JKBX is not the first company to do something like this—in fact, over the years I’ve advised a similar company called Upfront Capital on how to integrate analytics into their investment platform. (Co-Founders Anthony Caesar and Alairé Jameson have put a lot of thought and care into their platform, so if you’re interested in retail music investment, start with Upfront.)

Disrupting streaming with a Robinhood-like platform is a ways off, so for now, streaming remains the primary source of royalty generation, and that brings to light the question of value distribution for artists, labels, publishers, and, increasingly, investors. With more and more stakeholders taking an interest in how musicians make money from streaming, it’s worth breaking down 1) how much music is actually worth and 2) what people actually mean when they say artist-centric, user-centric, or pro rata.

Music is almost worthless now, but access isn’t.

By now, we’ve probably all heard that $.004 per stream number that gets bandied about, and for good reason. I’ve crunched the numbers on my own music, and it seems to be about right. While that might be what gets paid out per stream, that’s not actually what a stream is worth in terms of the value it represents to US recorded music.

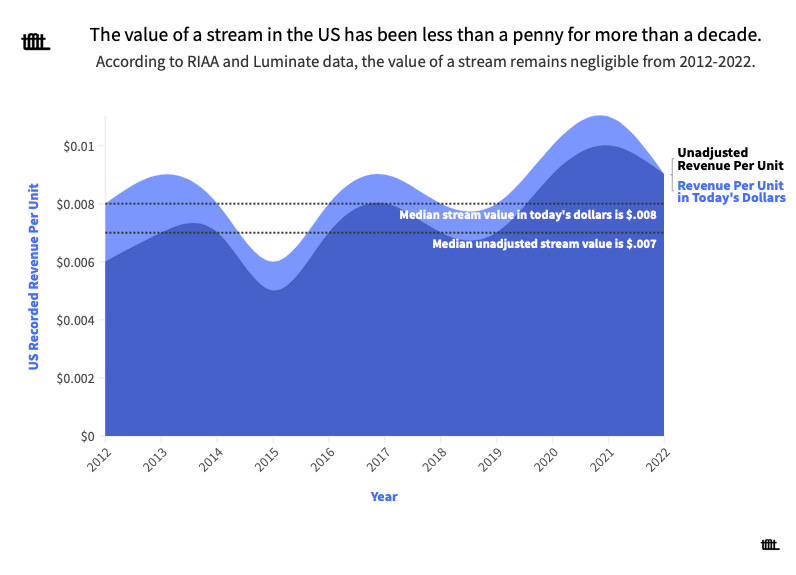

If we divide the amount of revenue generated by streaming subscriptions and advertising in the US by the number of total on-demand streams in the US, we get an estimate of about $.008 per stream over the last 10 years. While there is a slight upward trend in the graph above, the revenue per unit is so marginal that it’s hard to say an increase from $.008 to $.009 over 10 years is a significant change in value. In effect, when it comes to streaming consumption in the US, not only is average revenue per unit (ARPU) less than a penny, but it has been that way from the start.

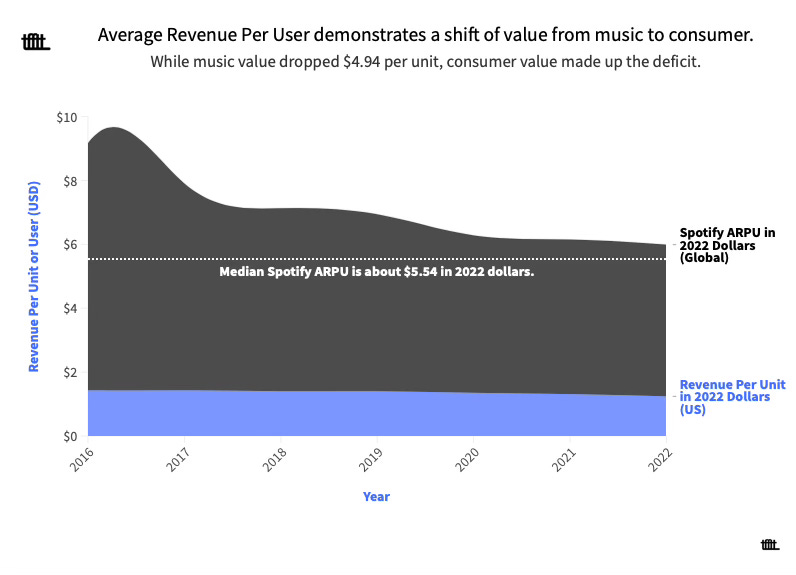

The contemporary worthlessness of music should not be surprising, because music, for the most part, is no longer the thing being sold—access is. The “U” in ARPU now means “user” and not “unit,” because you are the “U” being measured. As a result, trying to compare the value of a track today to the value of a track before streaming is, to use a tired metaphor, comparing apples and oranges. Still, it’s useful to illustrate this drop in value for dramatic effect.

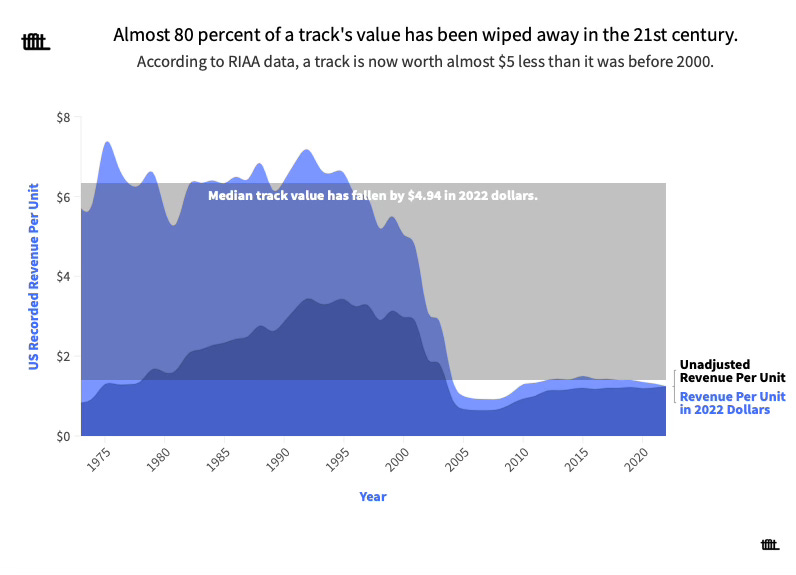

Dividing the US recorded revenue generated by vinyl, cassette, CD, and digital download singles by the number of units sold puts the “decommodification” of music on full display. Before 2000, a single was worth about $6.34, adjusted for inflation. After 2000, a single was worth about $1.40, adjusted for inflation. That means the value of a track has effectively dropped by almost $5 with the decline of physical and the rise of streaming.

That doesn’t mean that value has just disappeared. Instead, that value has transferred over to the consumer in the streaming era. To make a dubious apples to elephants comparison, Spotify’s global ARPU is about $5.54, which, when added to whatever minimal music value there is left, puts us back to the near $7 revenue per unit we saw during the physical era, making up for the dramatic music value loss from the graph above.

That said, it is apparent that Spotify’s ARPU has declined in the last six years, which is a big reason they recently decided to increase their prices. Provided there isn’t major churn—and TikTok Music doesn’t launch at a much lower price point—this price increase will lift ARPU in the short-term. However, with an infinite supply of music and a finite addressable market, dilution will continue to be an issue in the long-term—especially under the pro rata royalty distribution model.

Maybe a diversity of streaming models is a good thing.

There is a lot of conversation right now about how royalties should be distributed on streaming platforms, with many people seeming to advocate for one model over another. If platforms like JKBX and Upfront Capital take off, this conversation is only going to escalate, because consumers themselves will have a stake in royalty distribution.

With that in mind, I’ve become convinced that framing the discussion in terms of a singular model is misguided. As streaming evolves, we should start considering DSPs as different formats, much like we did with vinyl, cassettes, CDs, and digital downloads. Each DSP increasingly provides a different listening experience, serves a different audience, and accounts to artists in different ways. Just like you wouldn’t pay the same price for vinyl and a digital download, you probably shouldn’t pay the same price for access to each DSP. Unfortunately, DSP price diversity probably isn’t happening any time soon, so royalty distribution diversity will have to do for now.

With each DSP working with the same price point, the amount of revenue available for distribution is dependent upon the user base. It’s not that one royalty distribution model is necessarily better than another; rather, each model serves a different purpose, because each DSP serves a different user base, both in terms of volume and kind.

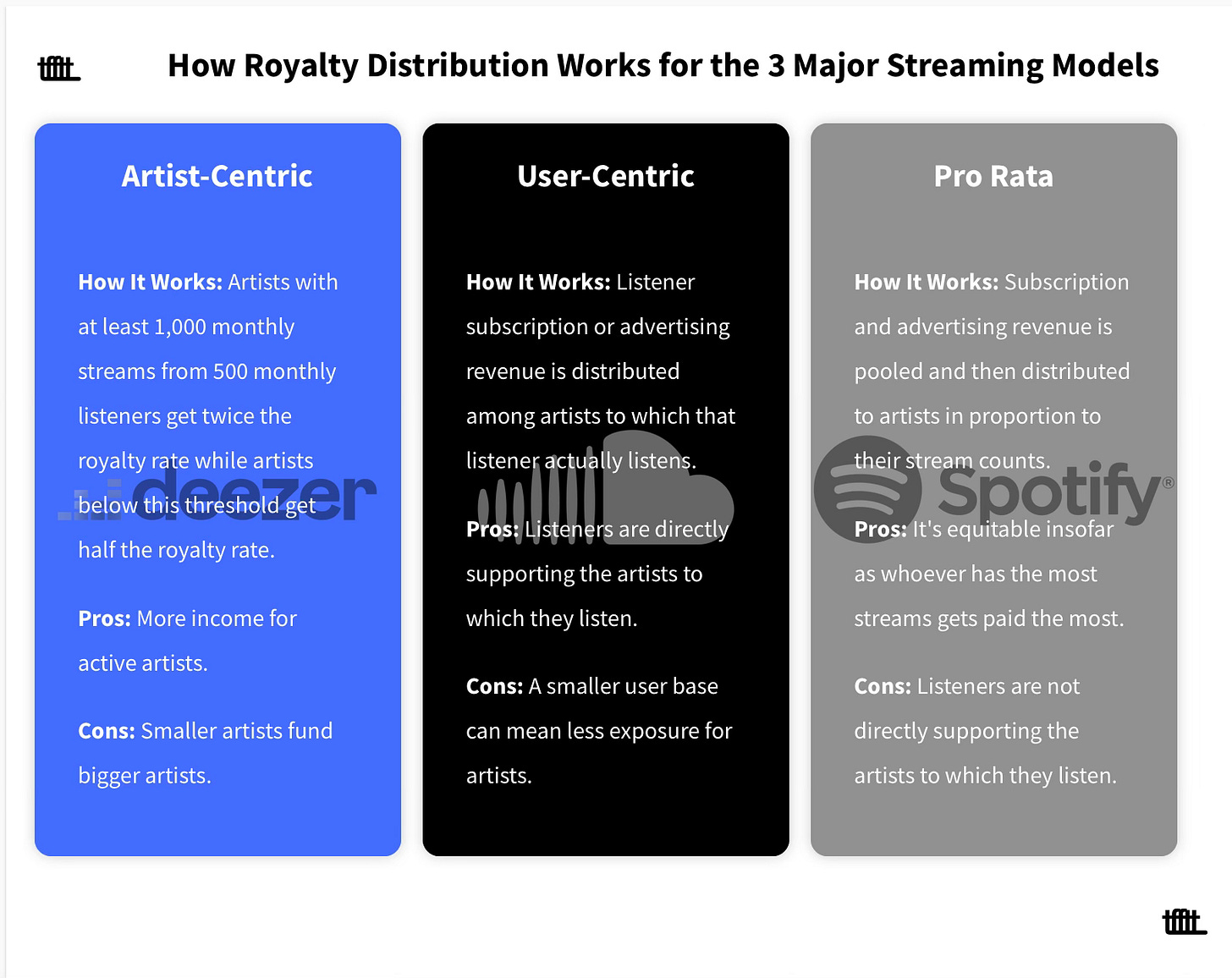

The artist-centric model, which Deezer recently announced in partnership with Universal Music Group, halves the royalty rate for artists with less than 1,000 monthly streams from 500 monthly listeners and doubles the royalty rate for artists performing above that threshold. It also rewards active streams (vs. algorithmic streams) with an additional double royalty rate.

The user-centric model, which SoundCloud announced as “fan-powered royalties” in 2021, distributes revenue directly according to which artists a user listens to.

The pro rata model, which Spotify pioneered and most other DSPs subsequently adopted, pools revenue and distributes it according to how many streams an artist accrues.

The artist-centric model helps to increase income for active artists and filter out noise, but it also arguably takes income from smaller artists and gives it to bigger artists. The user-centric model rewards artists with active listeners and fans, but there’s also less opportunity for exposure to a wider audience base. The pro rata model distributes most revenue to superstars, because they have the most streams, which can create a system of perverse incentives.

The important thing for artists (and someday, consumer-investors) to understand is that DSPs aren’t created equal, so it might be worth thinking about how to make the most of streaming royalties on each platform: Maximize consistent conversion on Deezer, drive up engagement on SoundCloud, and expand reach on Spotify.

There are plenty of other active and proposed models out there, including Resonate’s stream-to-own model and Mark Mulligan’s artist- and user-centric amendments, but the reality is musicians—especially independent musicians—still won’t really make all that much from streaming. In fact, there’s a distinct and very dystopian possibility that consumers could soon make more from streaming than musicians do. Yesterday, consumers paid for a product. Today, consumers pay for access. Tomorrow, consumers will pay for—and earn from—participation.

Information is abundant, and time is not—but that doesn’t mean we should only see the trees. The proliferation of information should help us see the forest.